NOTE: `e^-` is shorthand for electron.

From the previous post on `e^-` configuration, we learned that orbitals are not round circles but rather several different shapes that describe where an `e^-` is likely to be. An atomic orbital only describes the probability of where an `e^-` should be. If this sounds foreign or unclear, go back and re-read the section on Schrodinger's Equation. This brings us to the concept of a node.

Just like how orbitals describe where an `e^-` is likely to be, nodes describe where `e^-` are unlikely to be. In the following image, the white regions are nodes. In these regions, we can say that no `e^-` exist.

This kind of node is called a radial node. Radial nodes exist at a certain radius from the nucleus.

The node to the top is called an axial node. This kind of node is a plane or cone.

It's usually not too difficult to determine if a node is radial or axial. If the node exists only at a certain distance, then it's radial. Otherwise, it's axial. In just a few paragraphs, we'll learn how to figure out how many of each node exists. For now, just know that:

1. Nodes are where no `e^-` exist.

2. There are 2 types of nodes: radial and axial.

We referenced spin very briefly when discussing the Pauli Exclusion Principle and Hund's Rule. Recall that any single orbital can hold at most 2 `e^-`. Spin is what we use to distinguish the `e^-` in a given orbital. The two possible values of spin are `+1/2` and `-1/2`. In other words, if there are two `e^-` in an orbital, one of them will have spin `+1/2` and the other will have spin `-1/2`. You can visualize spin by imagining one of the `e^-` spinning upward and the other spinning downward.

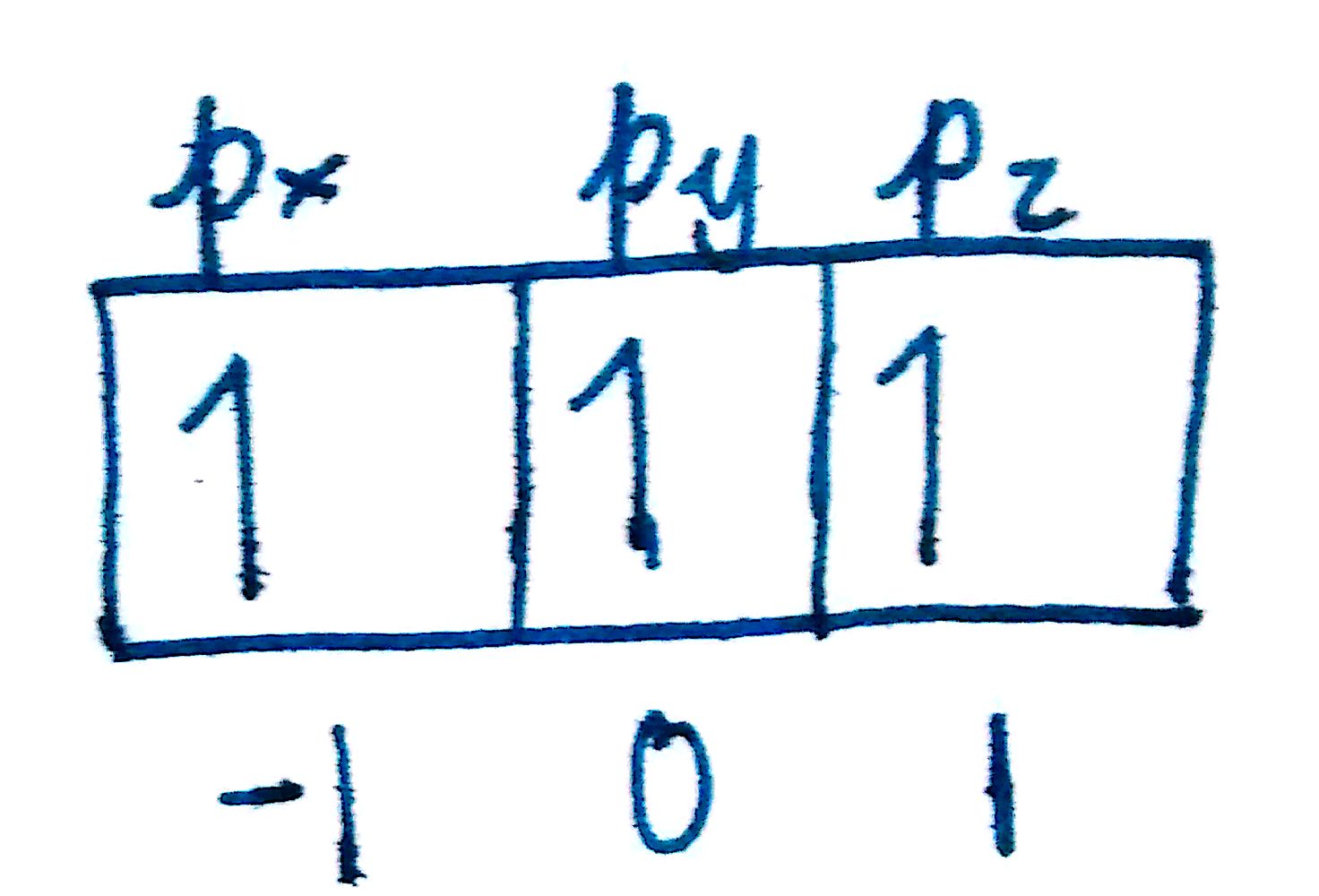

We used a similar diagram to represent the set of p-orbitals in the post on `e^-` configurations. Each box represents a subshell of the p-orbitals. All together, they represent a set of p-orbitals. An upward spinning arrow represents `+1/2` spin. Similarly, a downward spinning indicates `-1/2.` In the `p_x` orbital, the total spin is `+1/2+(-1/2)= 0`. In the `p_y` and `p_z,` the total spins are `+1/2` for each one, since there is only 1 `e^-` spin up.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle states that 2 `e^-` in a given orbital must have opposite spins. In other words, one must be spin up and the other spin down.

Hund's Rule states that orbitals will fill in a way to maximize spin. In the diagram above, the spins (`+1/2-1/2`) in the first orbital cancel out. Thus, `e^-` will always fill 1 `e^-` in each orbital before filling in the 2nd. For example, in a set of d-orbitals:

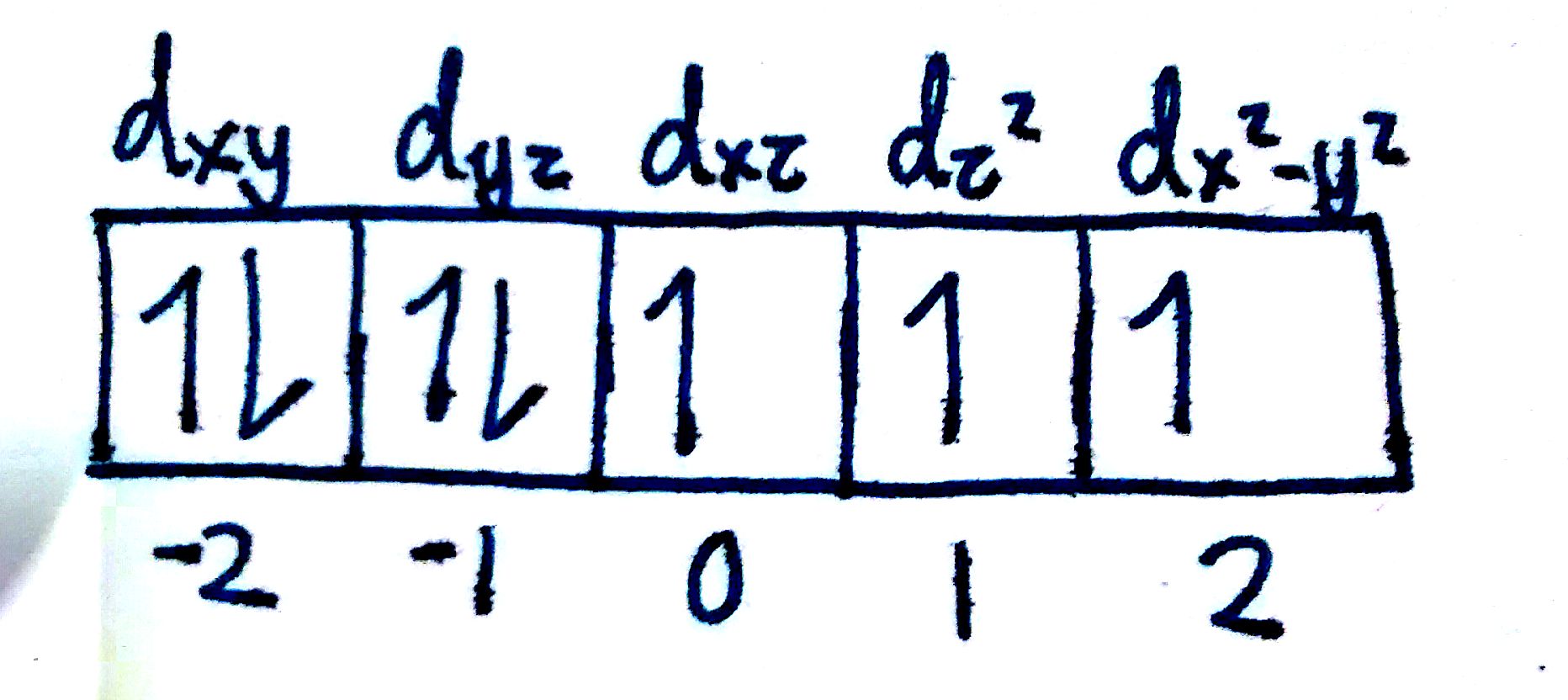

Each box corresponds to a different d-orbital. All 5 boxes together represent an entire set of d-orbitals. Note that there are 6 `e^-` in each case.

According to Hund's Rule, orbitals will fill in whatever way maximizes total spin. Clearly, #1 has the highest spin. Therefore, when filling the d-orbitals with 6 `e^-`, the `e^-` will fill the way that #1 does and not the ways shown in #2 & #3.

Since these rules for `e^-` configuration are vital in chemistry, let's review them one more time before moving forward.

#1. The Pauli Exclusion Principle: If there are 2 `e^-` in any given orbital, the 2 `e^-` must have opposite spins. These spins are denoted by `+1/2` and `-1/2.`

#2. The Aufbau Principle: `e^-` will fill from lowest energy level to the highest.

#3. Hund's Rule: Orbitals will fill to maximize total spin. In other words, `e^-` will fill a set of orbitals with 1 `e^-` in each before filling in the 2nd `e^-`.

With these principles now understood, we can move onto the 4 quantum numbers.

Imagine if you had a pile of coins laying on a coordinate grid.

Sorry for the bad drawing, real coins are expensive (I'm just too lazy to go find some). Now imagine we wanted to describe the properties of the coins on this grid. There are 4 characteristics that would be fairly easy to use

1. x-coordinate

2. y-coordinate

3. Color of coin

4. Writing on coin

With these four properties, we can describe any coin on the grid. To condense these four properties, we can write them as a set of {x, y, color, writing}. For example, if I gave you the set

{3, 2, blue, 0.10}

You would know that I was referring to the blue 0.10 coin at (3,2) Note that this set of descriptions can only describe one coin. Related to this, check out the two canadian coins. They're both the same coins, but at different locations. One is described by {1.5, 1, red, Canada} and the other {4, 2, red, Canada}. Therefore, we can say that coins can share properties, but not all 4 properties.

Quantum Numbers operate on the same principles, only instead of describing coins, we're describing the `e^-` in a given atom. With the vast number of `e^-` that can exist in an atom, we need some way of distinguishing each electron. Just like with coins, no two `e^-` in a single atom can have the same set of quantum numbers. Quantum Numbers describe the properties of a single `e^-`. There are 4 quantum numbers for any given `e^-`.

The Principle quantum number, `n`, tells us the energy level and size of the orbital containing the `e^-`. In other words, the larger the `n`, the higher the energy level, and the larger the orbital itself. Consider the s-orbitals shown:

The 1s is clearly smaller than the 2s, which is smaller than the 3s. The number in front of the s is the principle quantum number. Revisiting the Aufbau Principle, the 1s orbital should fill before the 2s, which should fill before the 3s. The `e^-` configuration of any atom will show that this is true:

The Angular Momentum quantum number, `l`, tells us the type of orbital. Recall that we went over 3 different types of orbitals: s, p, & d.

The s-orbitals look like the spherical red one, p-orbitals the dumbbell shaped yellow ones, and d-orbitals the cloverleaf/donut shaped blue ones. The `l` value tells us what shape of orbital the `e^-` we're looking at is in.

`l=0` is an s-orbital

`l=1` is a p-orbital

`l=2` is a d-orbital

`l=3` is a f-orbital

Therefore, if I were to say that an `e^-` has `l=1`, I would be saying that the `e^-` is in a p-orbital. Additionally, the `l` value is related to the `n` value through the following relation:

`l=0,1,2...(n-1)`

In other words, the largest the `l` value can be is `n-1`. If you had `n=2`, the `l` could only be equal to `0 and 1`. Since this corresponds to 2s and 2p orbitals, we know that the 2d orbital cannot exist. Similarly for `n=1` the highest the `l` value could be is `n-1`=`0`, therefore `l=0`. Therefore, at the `n=1` energy level, only the 1s orbital exists.

Note that the `l` value is a series of possible values and not just the `(n-1)` value. For `n=4`, we have `l=0,l=1,l=2`, and `l=3`. This means we have 4s, 4p, 4d, and 4f orbitals!

When doing electron configurations, we noted that the first d-orbital was the `3d`. The angular momentum quantum number explains why this is. In order for a 2d to exist, `n=2` and `l=2`. This violates the relationship and therefore no 2d exists. The first d-orbital is the 3d. The first f-orbital is the 4f. Write out the `n` and `l` quantum numbers to make sure you understand why.

The Magnetic quantum number, `m_l`, tells us which subshell in an orbital an `e-` is in. The rule for `m_l` is the following:

`m_l=-l...0...l`

(Those are `l`-s and not one)

Let's do an example to help illustrate this.

#1. Write out the `n,l,` and `m_l` for a 2p orbital.

We know that the `n=2` and `l=1`. Since `m_l` ranges from `-l to l`, the `m_l` values can be `-1,0, and 1`. Each of these indicates a different one of the p-orbitals. Since there are three p-orbitals (`p_x,p_y,p_z`), there must be 3 `m_l` values.

To denote the `e^-` in the `p_x` orbital, we would say `n=2, l=1 and m_l=-1`. Think of a car with 5 seats. In order to tell someone which seat you want, you'd say something like "shotgun" or "middle back-seat." The car in this analogy is the set of orbitals and the description of the seat is the `m_l`.

Answer: `n=2, l=1, m_l=[-1,0,1]`

#2. Write out the `n,l,` and `m_l` for a 4d orbital.

`n=4` off the bat. For a d-orbital, `l=2`. Therefore, the `m_l` can be one of `-2,-1,0,1,2`.

Just like with the p-orbitals, the d-orbitals is a set of orbitals. Instead of 3 orbitals though, the d-orbital is a set of 5. This means that we need 5 `m_l` to distinguish each one. Fortunately for us, we have exactly 5 quantum numbers!

If I wanted to designate the `e^-` in the `d_z^2` orbital, I would give the following set of quantum numbers:

`n=4, l=2, m_l=1`

Note that the number corresponding to each orbital is completely arbitrary. We could've labelled the `d_z^2` as -2, or 0. The important thing is that each `m_l` value denotes a different subshell.

Answer: `n=4, l=2 ,m_l=[-2,-1,0,1,2]`

The final quantum number is something we've gone over previously in this post. The only values of spin are `+1/2` and `-1/2`. If there are two `e^-` in the same orbital, they must have opposite spins. By convention, the first `e^-` is `+1/2` and the second `e^-` is `-1/2`.

This completes our discussion of quantum numbers. You can think of the quantum numbers as analogous to a description of a car:

1. `n` is the size of the car. The bigger the `n`, the bigger the car.

2. `l` is the type of car. The car can be a sedan, a pick-up truck, a motorcycle, etc.

3. `m_l` is the specific seat in the car. If there are 5 seats in the car, there must be 5 `m_l` to distinguish each seat.

4. `m_s` is something I'm not clever enough to think of. In other words, I'm unable to think of a clever analogy. Let me know if you're able to!

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Possible Values |

Principle |

`n` |

`1,2,3...` |

Angular |

`l` |

`n-1` |

Magnetic |

`m_l` |

`-l...0...l` |

Spin |

`m_s` |

`+1/2, -1/2` |

Now that we know our quantum numbers, we can relate the number of nodes to this number:

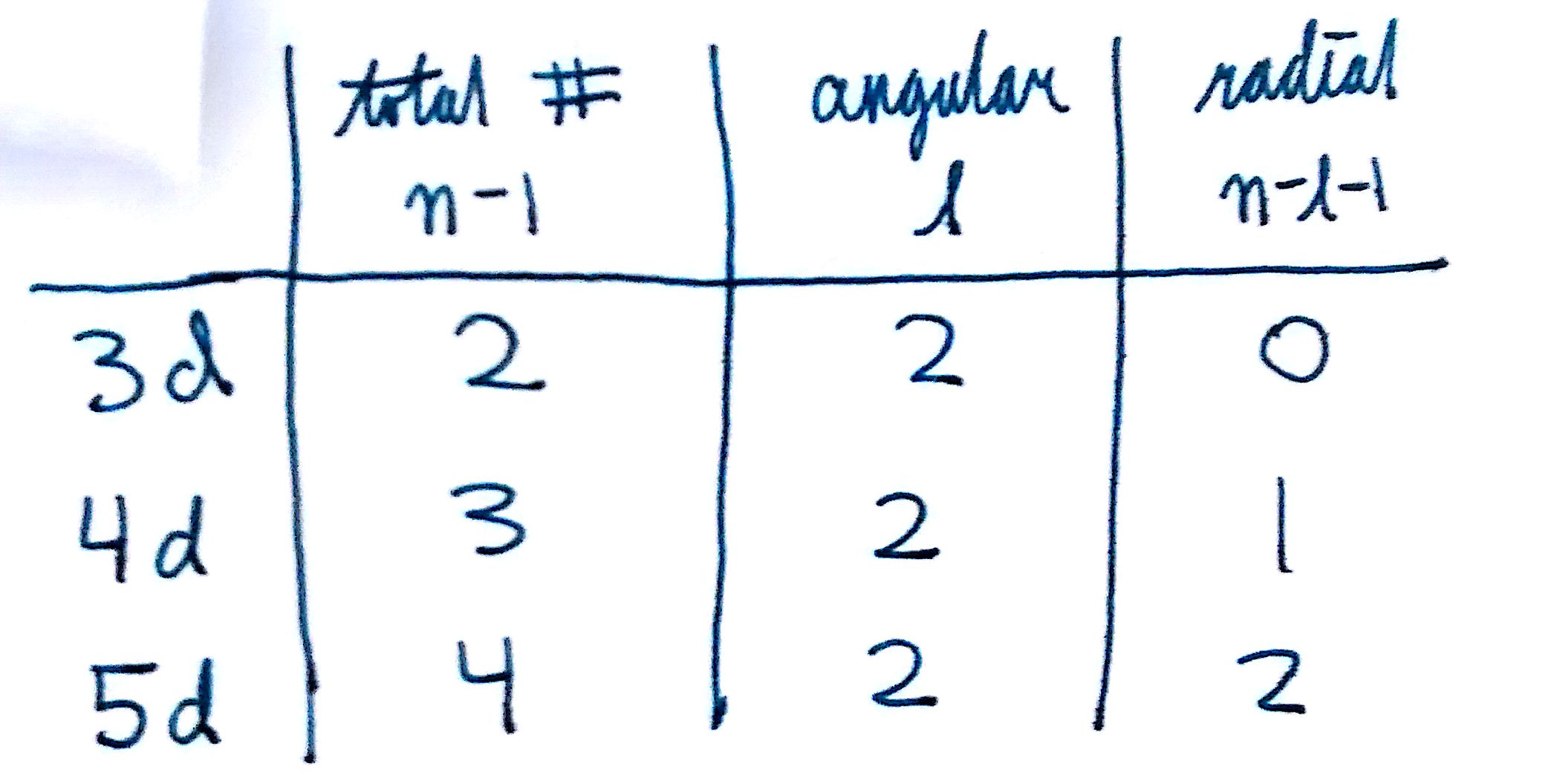

The total number of nodes = `n-1`

A 3s orbital has 2 nodes. A 4p orbital has 3 nodes. To determine what types of nodes they are:

The number of axial nodes= `l`

A 3s orbital has 2 nodes. Since `l=0`, the number of axial nodes is 0. A 4p orbital has 3 nodes. Since `l=1`, the number of axial nodes is 1.

The number of radial nodes is whatever's left over: `n-l-1`

A 3s orbital has 2 nodes. Since `l=0`, the number of axial nodes is 0 and the number of radial nodes is 2. A 4p orbital has 3 nodes. Since `l=1`, the number of axial nodes is 1 and the number of radial nodes is 1.

The number of axial nodes for a specific orbital will remain constant.s-orbitals will always have 0 axial nodes, p-orbitals 1, and d-orbitals 2. When you increase the principle quantum number (`n`), you increase the number of radial nodes.

For example, compare the number of nodes in a 3d orbital to 4d and 5d orbitals. Now that you're able to solve for the number of radial and axial nodes, see if you can identify the different nodes for certain orbitals! Look up images of a couple different orbitals and identify all the radial and axial nodes to see if the numbers match up with your predictions.

#1. Write out the quantum numbers for an `e^-` in a 3s orbital.

#2. Demonstrate using quantum numbers why the 1f, 2f, and 3f orbitals do not exist.

#1. `n=3, l=0, m_l=0, m_s=+1/2`

#2. For the 1f orbital, `n=1` and `l=3`. Since `l` can only be up to values of `n-1`, the highest possible value of `l` is 0. For the 2f and 3f, the same principle applies: the `l` cannot be greater than `n-1`.

1. Electrons are now abbreviated as `e^-`.

2. Nodes describe where an electron cannot exist.

3. The 4 quantum numbers are a description of a specific `e^-` for an atom. No two `e^-` in the same atom can have the same 4 quantum numbers.

4. The total number of nodes is given by `n-1`. The number of axial nodes is given by `l` and the number of radial nodes is given by `n-l-1`.