Both thermodynamics and kinetics give us information about a given process. While both are useful and integral to an understanding of chemical processes, they fulfill different purposes. Thermodynamics tells us about which way a process/reaction is likely to occur whereas kinetics tells us the rate at which the process/reaction will occur. For example, consider the phase transition of carbon from its diamond form to graphite:

`"Diamond" ↔ "Graphite"`

`DeltaH=-1.9"kJ"`

`DeltaG=-2.9"kJ"`

Thermodynamics says that this reaction is favored, in both `DeltaH` and `DeltaG` (which we have not covered yet). If this is true, then all the diamond in the world should be graphite, the material that pencil lead is made out of. Why is it then that diamonds still exist?!

Fortunately for those who own diamonds, it turns out that the rate for this reaction is practically 0. In other words, while the reaction is happening, it's happening at such a slow rate that it's practically not happening at all. The takeaway from this is that while a reaction may be thermodynamically favorable, it may not be kinetically favored. In other words, even if thermodynamics says a process is going to happen, the process may happen so slowly that, for all purposes, the process is not happening at all. In this section, we're going to look at the thermodynamics component of whether a reaction will happen or not.

Spontaneity

A process is said to be spontaneous if, given no outside intervention, the process will occur. The reason I use the term process instead of reaction is because spontaneity applies to all processes, including chemical reactions. For example, if one leaves a ball at the top of a hill, it will spontaneously roll down without anything acting on it. This is an example of a physical process that is spontaneous. Another example is gas being introduced into a room: the gas will spontaneously diffuse throughout the room until its evenly distributed.

To help understand the concept of spontaneity, try labeling each of these processes as spontaneous or not:

a) A deck of cards being shuffled into the original order.

b) Heat flowing from a hot region to a cold region.

c) An iron nail rusting.

b & c are both spontaneous processes because they'll happen without any outside intervention. a, while possible, is very unlikely to happen.

Entropy

Entropy `(S)` is a concept that's intimately tied in with spontaneity. By itself, entropy is an abstract concept that is commonly taught to be synonymous with "disorder" or "randomness." These are appropriate for the level of detail covered in this course, so we'll stick to them for now. In the Fun Facts section, I'll go over some "better" descriptions of entropy.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of the universe can only increase. In other words, the universe can only become more and more disordered as time goes on. Mathematically, this is expressed as `DeltaS>0`.

If you think of your room as the universe, this makes sense; your room naturally becomes messier over time as clothes are left on the floor, dust collects, etc. The way this ties into spontaneity is that all spontaneous processes are just processes that are driven by an increase in entropy. For example, when gas diffuses throughout a room, it is doing so because the diffusion increases the entropy of the universe .

Notice that the Second Law says that the entropy of the universe must increase, but says nothing about local entropies. It is certainly possible for a part of the universe to become more ordered - the Second Law only states that the overall entropy must increase. The way we think about this is by splitting up entropy in terms of the "system" and the "surroundings." The system is going to be the part of the universe that we're examining while the surroundings is everything else. The two are related to the universe through the following:

`"System" + "Surroundings" = "Universe"`

According to the Second Law, only the entropy of the universe must increase. This means that the entropy of the system can decrease, as long as the entropy of the surroundings increases enough to compensate. As mentioned above, we can express this as:

`DeltaS_"universe">0`

And since the Universe is equal to the System + the Surroundings, we can rewrite it as:

`DeltaS_"system"+DeltaS_"surroundings">0`

In more relatable terms, you can always clean your room (decrease the entropy of the system), but in the process you're going to generate trash (increase entropy of surroundings). This results in the world as a whole becoming messier despite your room being cleaner.

Positional Interpretation

One way of imagining entropy is that entropy corresponds to positional availability. Imagine two small boxes of the same size, one with a small amount of solid and the other with the same mass of solid in gas form. Will the solid or the gas have a higher entropy?

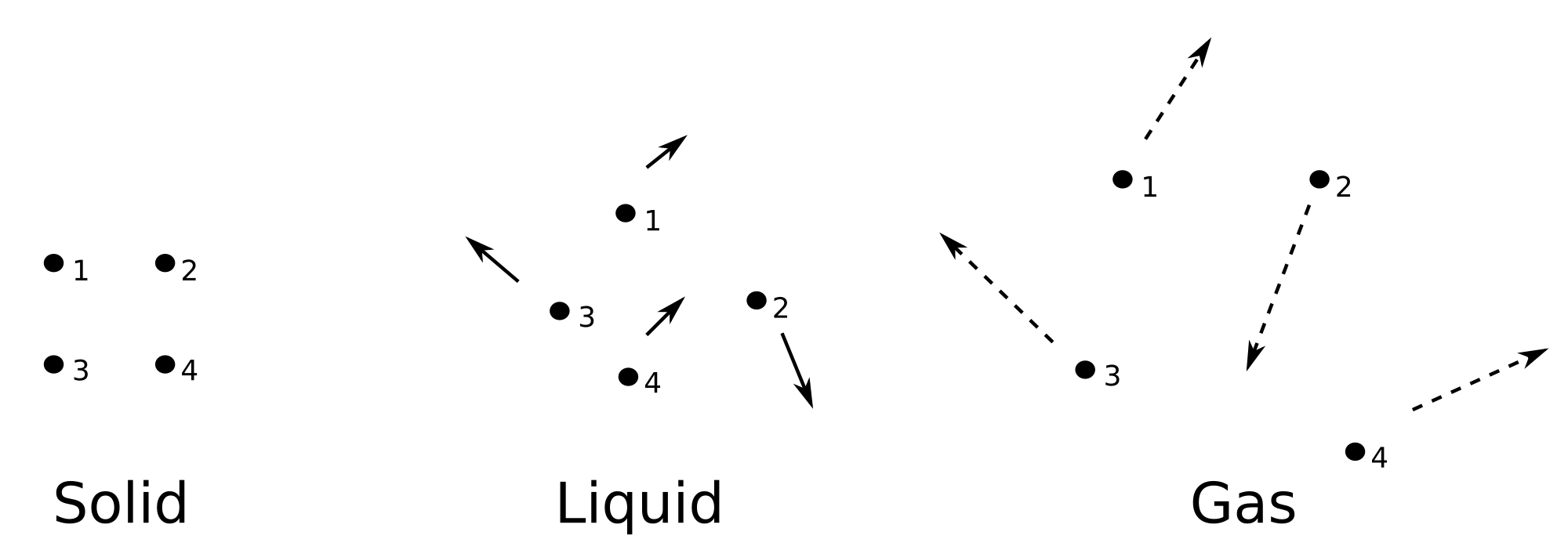

The positional interpretation of entropy says that the more positions there are that can be occupied, the higher the entropy. Since the gas particles can be dispersed everywhere throughout the box while the solid sits in a small portion of the box, the gas will have higher entropy!

A general statement can be made that the entropy of solids is less than the entropy of liquids, which is less than the entropy of gases:

`S_"solid"<S_"liquid"<S_"gas"`

The reason for this is that the more spread out the molecules are, the more positions they can occupy and thus the more disorder there can be. If the molecules are packed closely together as in a solid, then the disorder is limited becuse the atoms are "stuck." On the other hand, if the molecules are spread apart, the disorder is significantly larger since the molecules can now occupy a variety of different spaces. This can be seen in the following diagram:

To give an idea of how large the difference in entropy in states is: the entropy of ice is `(41 "J")/("mol"*"K")` , liquid water `(69.9 "J")/("mol"*"K")` , and water vapor `(188.7 "J")/("mol"*"K")` . The entropy of water vapor is more than 4 times the entropy of ice!

Changes in Entropy `(DeltaS)`

Changes in Entropy `(DeltaS)`

Let's say that a given reaction has a change in entropy, `DeltaS` , that's positive. Is that reaction going to occur according to entropy? Remember that `Delta` means `"Final"-"Initial"` , so a positive `DeltaS` indicates that the final state has more entropy than the initial state. Since the entropy is increasing, we know that the reaction is entropy favored. Conversely, if a reaction has a change in entropy that's negative, the reaction is not favored according to entropy.

Consider the following processes and determine whether they cause an increase or decrease in entropy:

a) A brand new deck of cards being shuffled

b) `NO_((l)) ⇒ NO_((g))`.

c) `H_2O_((l)) ⇒ H_2O_((s))`

a and b correspond to increases in entropy. In a, the deck is more "disordered" after being shuffled whereas in b, the entropy of a gas is higher than the entropy of its equivalent liquid. In c, entropy is decreasing since the entropy of a solid is less than that of the corresponding liquid state.

Summary

1. A spontaneous process is one that will occur without any outside intervention.

2. A spontaneous process is one that corresponds to an increase in entropy.

3. Entropy can be thought of as a measure of disorder.

4. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of the universe must increase.

5. The entropy of a system can decrease so long as the overall entropy of the universe increases.

Fun Facts

#1. Definition of Entropy

There's a fair amount of debate as to whether entropy should be taught as being synonymous with disorder or not. In reality, entropy does not have much to do with disorder. Definining it as such only helps us visualize it for certain scenarios, but for practical applications, the definition fails. The true definition of entropy is beyond the scope of this post, but we'll include it for fun. The definition of entropy according to thermodynamics is:

`∫ (dq_"rev")/T`

Where `q_"rev"` is the heat of a reversible process. This is the level of detail covered in a physical chemistry or thermodynamics course, so don't worry about it for now.