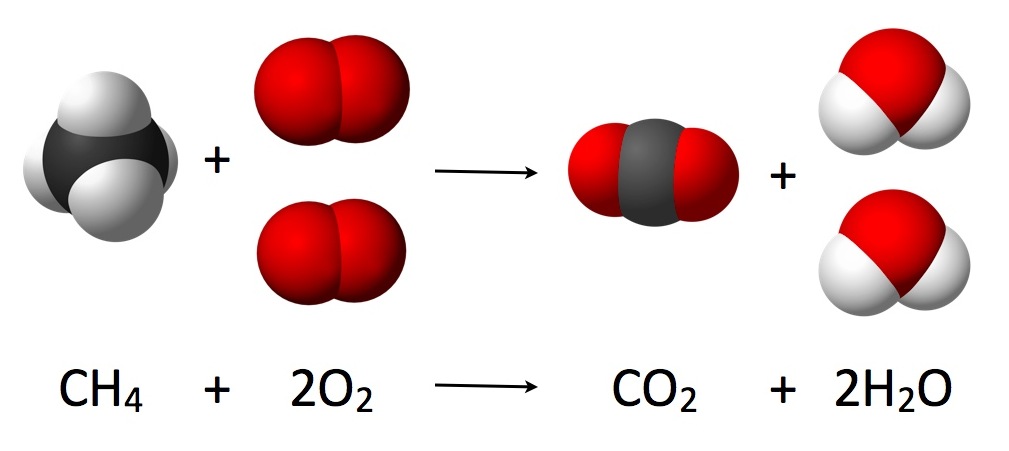

If you recall from Dalton's atomic theory, all chemical reactions are rearrangements of atoms. A chemical equation is what we use to describe a chemical reaction. The picture above is an example of one which reads that `CH_4` and `2O_2` will react to form `CO_2` and `2H_2O.` Additionally, Dalton's atomic theory provides the definition of a compound: a compound is a molecule consisting of two or more elements combined in specific ratios For example, `H_2O` is a compound because it contains H and O atoms in a 2:1 ratio. `Cl_2` is not a compound because it only contains chlorine.

`H_2O_((l))+Na_((s)) rArr NaOH_((aq))+H_2(g)`

This reaction in the video is the equation above and describes what happens when solid sodium comes into contact with liquid water: hydrogen gas is released which, given sufficient heat, ignites.

`N_(2(g)) +3H_(2(g)) rArr 2NH_(3(g))`

Another example is this chemical equation, which states that 1 mole of nitrogen gas + 3 moles of hydrogen gas will become 2 moles of `NH_3`, ammonia. In a way, chemical equations are like the recipes of chemistry.

Counting atoms may be tricky initially. Take for example the reaction for the synthesis of ammonia:

`N_(2(g)) +3H_(2(g)) rArr 2NH_(3(g))`

How many atoms of `N` are there on the reactants side? If you answered 1, you're wrong. It turns out that the subscript designates the number of atoms in the compound. In other words, the correct answer is 2. How about atoms of `H` on the right side? Since we have 2 molecules of `NH_3`, each with 3 atoms of `H` , we have a total of 6 atoms `H` on the right side. This is covered in the previous post, so check that out if you haven't already:

Here are a couple to test your understanding.

How many atoms of S are in `3 SO_2?`

3. There's 1 atom of `S` in each molecule of `SO_2.` Since we have 3 molecules of `SO_2`, we have 3x1=3 atoms of `S` .

How many atoms of O are there in `4 Fe_2O_3?`

12. There's 3 atoms of `O` in each molecule of `Fe_2O_3`. Since we have 4 molecules of `Fe_2O_3`, we have 4x3=12 atoms of `O`.

In order to make a meaningful recipe, one has to convey the exact amounts used in the ingredients and the final amount of product yielded. You wouldn't say to "mix some flour and egg to get a couple cakes," but rather something more like "mix 300g flour and 3 eggs to get a cake." Chemistry is the same way: we have to specify the amount of materials both in the beginning and end of a reaction. The calculation of this is called stoichiometry, which really sounds more intimidating than it should. Stoichiometry is really just multiplication and division with a purpose. The compounds and molecules in the left side of the equation are called the reactants and are the molecules that will be reacting with each other. The products are on the right side of the equation and are the molecules that form from the reactants.

`CH_4+2O_2 rArr CO_2+2H_2O`

In this reaction, `CH_4`, methane, and `O_2`, oxygen gas, are the reactants. When they react with each other, they form `CO_2`, carbon dioxide, and `H_2O`, water. The numbers in front of the molecules designate the number of moles of the molecule i.e `2CH_4` indicates 2 moles of `CH_4` . For molecules without a number, the number is implied; 1`CH_4` and 1`CO_2`.

These numbers tell us the ratio of molecules in the reaction. Since the reactants have `2O_2` and `CH_4`, the reaction requires 2 times more `O_2` than `CH_4`. Similarly, 2 times the `H_2O` will be produced as compared to `CO_2`, since `H_2O` has a 2 in front of it and `CO_2` doesn't. One way to think about this is that the number in front of the molecule is the amount of the molecule required. Going back to the cooking analogy, saying `2O_2` would be equivalent to saying 300 grams of flour. The number indicates the amount of the molecule required.

#1. In the reaction `N_2 + H_2 rArr 2NH_3`, how many moles of `NH_3` will be formed if 2 moles of `N_2` and 2 moles of `H_2` are used?

This is a lot simpler than you may think. Since `NH_3` has 2 times the moles as both `N_2` and `H_2` , the total number of moles `NH_3` will be 4 moles. The mathematical way of doing this is to create a conversion factor: `(2 "mol" NH_3)/(1 "mol" N_2), and (2 "mol" NH_3)/(1 "mol" H_2)`. We just use the numbers in front of the molecule to create a conversion factor. Therefore, the answer can be solved for mathematically.

We have `2 "mol" N_2` and `2 "mol" H_2`. The conversion will therefore be `(2 "mol" N_2)((2 "mol" NH_3)/(1 "mol" N_2))`, which cancels out to give us `4 "mol" NH_3`. We can do the same with `H_2` to get `4 "mol" NH_3`.

Answer: `4 "mol" NH_3`

#2. How many grams of `CO_2` are produced when 230 g of `Fe_2O_3` and `12.011 "g" C` react in the following equation: `2Fe_2O_3 + C rArr Fe +3CO_2`

This question is slightly different from the previous one, but at its core the approach to solving it is the same. Instead of asking for moles, we're asked for grams `CO_2.` The first step to any stoichiometry problem is to convert all quantities to moles. Let's first convert 320 g of `Fe_2O_3` and 12.011 g C to moles, using the molecular weight:

`MW_(Fe)= 2m_(Fe) + 3m_(C)= 2(55.85 "g"/("mol")) + 3(16 "g"/("mol"))=160 "g"/("mol")`

`MW_C=m_C=12.011 "g"/("mol")`

If you need a refresher on how to find the molecular weight of a compound, follow this link:

Now we can convert from grams to moles using the conversion factors:

`(320 "g" Fe_2O_3)((1 "mol")/(160 "g"))=2 "mol" Fe_2O_3`

`(12.011 "g" "C")((1 "mol")/(12.011 g C))=1 "mol" C`

This is good, seeing as the moles `Fe_2O_3` should be twice as much as the moles C. Now that we have the number of moles of the reactants, we can determine the number of moles `CO_2` formed:

`(2 "mol" Fe_2O_3)((3 "mol" CO_2)/(2 "mol" Fe_2O_3))=3 "mol" CO_2`

Just to check if it works, we'll do the same conversion using the other reactant; just because we can:

`(1 "mol" C)((3 "mol" CO_2)/(1 "mol" C))=3 "mol" CO_2`

In total, we get 3 moles of `CO_2`. Now we just have to convert `CO_2` to grams:

`MW_(CO_2)=m_c+2m_O=12.011+2(16)=48.011 "g"/("mol")`

`(3 "mol" CO_2)((48.011 "g" CO_2)/(1 "mol"))=144 "g" CO_2`

Answer: `144 "g" CO_2`

One of the things you must take note of when reading chemical equations is the Law of the Conservation of Mass, which states that mass can neither be created nor destroyed. In the context of stoichiometry and balancing chemical equations, the law just means that the amount of mass you end up with must be the same as the amount you had when you started. In other words, if I start off with 50g of reactants, I must end up with 50g of products. This may seem like a really obvious statement, but the formalization of the statement allows for us to be able to solve for some cool things. For example:

`C_3H_8+XO_2 rArr 3CO_2 +4H_2O`

What number must X be? We know that the number of atoms for each element must be the same on both sides. This means that if there are 3 `C` on left, there must be 3 `C` on the right. In this example, we have 3 `C` , 8 `H` , and `X/2` `O` on the left, and 3 `C` , 8 `H` , and 10 `O` on the right. Since the number of `O` must be the same on both sides, X=5!

The way we express this in chemical equations is by balancing the equation. This simply means that we write the equation in a way such that the number of atoms for all elements are the same on both sides of the equation. For example:

`Fe+O rArr Fe_2O_3`

is not a balanced equation; there's 1 `Fe` and 1 `O` on the reactants side, whereas there's 2 `Fe` and 3 `O` on the products side. In order to balance this, the number of `Fe` and `O` must be the same on both sides:

`2Fe+3O rArr Fe_2O_3`

Now we have `2` Fe on both sides, and 3 `O` on both sides. The equation is balanced. Here's a fun simulation to visualize what's going on when equations are balanced

Here are a few problems for practice.

#1. Balance the following reaction: `SO_2+O_2 rArr SO_3`

We have 1 `S` and 4 `O` on the reactants side. On the products side, we have 1 `S` and 3 `O` . Since the number of oxygen atoms is different, we have some balancing to do. To balance this equation, we're going to balance each element one at a time. In this case, `S` is already balanced so we just need to balance the `O` . Multiply the `O_2` by 2 and the `SO_3` by 2:

`SO_2+2O_2 rArr 2SO_3`

Now we have 1 `S` and 6 `O` on the left side, with 2 `S` and 6 `O` on the right. Since the `S` are now unbalanced, we have to balance them again. Multiply the left side by 2:

`2SO_2+2O_2 rArr 2SO_3`

Left side now has 2 `S` , 8 `O` . Right side has 2 `S` and 6 `O` . We just have to remove 2 `O` from the left side to balance the equation. To do this, dividing the `2O_2` by 2:

Answer: `2SO_2+O_2 rArr 2SO_3`

The equation is now balanced! The way that we did this may seem rudimentary, and that's because it is. Unfortunately, balancing chemical equations by hand is just a matter of stumbling around until a certain combination of numbers work. Fortunately, the stumbling becomes second nature over time. For balancing chemical reactions to become second nature, you have to do a lot of them. Over time you'll be able to balance them without even writing down the equation (if they're simple enough).

1. A compound is a molecule consisting of two or more elements. Examples of compounds are `NO` , `H_2O`, and `NH_3`.

2. A chemical equation describes what happens when certain molecules react under certain conditions. The left side is the starting molecules, called the reactants, and the right side is the ending molecules, called the products.

3. Stoichiometry makes solving for amounts of things sound more difficult and scientific than it actually is.

4. The subscript on molecules indicates the number of atoms in the molecule. For example, there are 2 atoms of H in the compound `H_2O`.

5. The law of conservation of mass indicates that, for any balanced chemical equation, the mass on the reactants side must be the same as the mass on the products side. Subsequently, the number of atoms for a given element must be the same on both sides.

6. Balancing chemical equations is a skill best learned through repetition and practice.

1. The Haber Process

`N_(2(g)) +3H_(2(g)) rArr 2NH_(3(g))`

This reaction is part of a series of reactions called the Haber Process and is responsible for the large-scale production of ammonia. Prior to the refinement of this process, ammonia was difficult to produce on an industrial scale. Because of this reaction, we're now able to produce industrial amounts of ammonia which can then be converted to fertilizer. This reaction is perhaps one of the most important reactions in the history of mankind as it has allowed us to grow mass amounts of produce. Fun story about Fritz Haber, the German chemist that the process is named after: he's currently known as the "father of chemical warfare" due to his research involving poisonous gases during World War II. For the most part, his research was geared towards explosives and poisoning people, but he inadvertently discovered a process that would end up tremendously benefitting mankind.